News

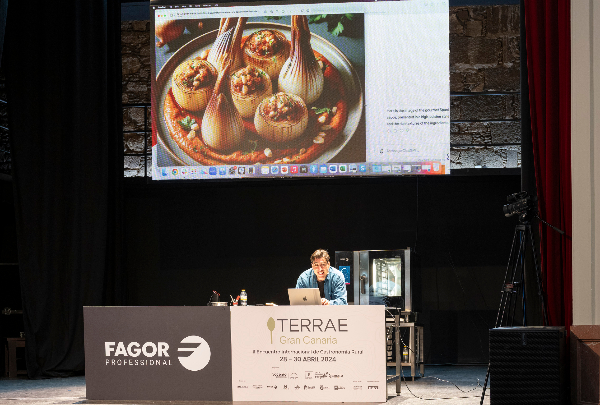

Responsible, empathetic and sincere dialogue between chefs, producers and administration.

Without produce, there is no cuisine, and without the countryside, there is no produce. Terrae presents this interesting and crucial debate in a round table discussion.

Francis Paniego, the fifth-generation chef at El Portal de Echaurren** (Ezcaray, La Rioja), has inherited many suppliers, but has also lost some due to a lack of generational succession. In order to maintain this network of small artisanal producers, he calls for "a responsible, sensitive and sincere dialogue with them, so that we chefs know our suppliers very well and are aware that there are things that must be paid as they deserve". He cites the example of Goyo, his goat's milk supplier, or "the Fany butcher's shop in Ezcaray, which closed down after supplying three generations with a 'magical' blood sausage, eliminating an emblematic product". "If we want to give coherence to our discourses, we have to establish close contact with the supplier," he said, even working together on the development of the product.

Paniego acknowledges that it is not easy to maintain a territory. "Our area is one of the most depopulated in Europe, and that is an added difficulty. But what I hear, especially from livestock farmers and people in the countryside, is that the administration adds many more difficulties to their daily work, such as excessive bureaucracy," he complains, admitting to a certain envy of the Basque Country, "where I think the small artisanal producer is more listened to. Because for the chef it is very important to support the creation of tangible goods, especially in small towns where there is a need to generate their own resources from nothing", encouraging chefs to "give a voice to producers, aware of the enormous importance they have in rooting a network that populates our territories and generates wealth".

Juan Ocaña, a fourth-generation goat farmer from Crestellina (Casares, Málaga, Spain), who, at the age of 40, decided to reduce the family herd to one eighth in order to produce organically, has turned his Payoya goat farm, a heritage of the Málaga and Cadiz mountain ranges, into a reference point for the culture of sheperding.Dressed in his goatherd's outfit, he told Terrae that his aim is for "visitors to understand our reality in the countryside, because we need an aware consumer who appreciates our product". To this end, he believes that the chef has a very important role to play, because "in addition to supporting the local product, he makes our work known to the consumer, and that leaves us time to continue our work in the countryside".

On the subject of generational change, which is a real threat to his profession, he acknowledges that technology is a very useful tool, "but even if today's animals wear GPS collars, we have drones or virtual fences, it will always be useful to know that the goat is walking in the wind to sniff out predators if you don't have cover," he warns with a touch of humour. But new technologies can indeed help to promote livestock farming by bringing young people closer to it, "because, as I told Minister Luis Planas, the goat is not in danger of disappearing, it is the goat farmer who is dedicated to it that will disappear. At this rate, we will have to see the goatherd embalmed in a museum," he joked again.

Support from the administration

For Rodrigo Castelo, chef at Ó Balcão (Santarém, Portugal), the kitchen helps to change the mentality of the producer. He knows this because he himself went from being a producer to a chef, which is why he fully understands that "we have to respect the producer a lot, listen to him, listen to him, because he is the one who will teach us the best way to understand each product in depth. What I want to do is cook every day, knowing every detail of the food I cook".

Another key for the Portuguese chef is the involvement of the administration in the development of the producer and the product. To this end, he cites the example of Portugal, where a few years ago, certain invasive species were threatening native species, such as lampreys or eels in fishing. "We decided to demand solutions from the administration, which has allowed the capture of this type of species, such as the hunting goose, which feeds on 8-9 kilos of fish a week from the Tagus," he said, explaining that he always warns clients about the hunting necessary to maintain the ecosystem, thus encouraging its consumption.

Isidoro Jiménez, a technician at the General Directorate of Livestock of the Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock, Fisheries and Food Sovereignty of the Government of the Canary Islands, who is also a master cheesemaker at the National School of Dairy Industry in Madrid, began his speech with the involvement of the administration. "A few years ago, this debate was unthinkable, because chefs were completely disconnected from cheese producers, who were marginal," he says. But he admits that this perspective has changed as the administration and the catering industry have realised what an exceptional product cheese is, "a change that has also contributed to a change in the mentality of the consumer, who has discovered a product that is a dish in itself". As for the lack of generational change, Isidoro concludes that "it's not just a question of liking the trade, it's a question of making it profitable. For this to happen, the product must be paid what it is worth, and for this to happen, the producer must know how to communicate what his product is worth," he concluded.